When I listen to my ultrasound, I can hear two heartbeats. One belongs to my son, and the other belongs to Samantha Whitney.

Samantha was a beautiful young woman and passionate about helping others. She told her parents when she got her drivers’ license that she wanted to register as an organ donor. A tragic accident took her life a few months later, and her decision saved my life.

I remember when I first heard my diagnosis: incurable heart disease. My doctor told me I probably wouldn’t live long enough to graduate high school. A heart transplant was my only chance. After I absorbed the shock, I asked her if I’d ever be able to have kids. She didn’t even answer, the possibility must have seemed so distant.

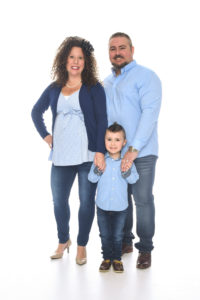

When I met Samantha’s parents, Al and Sandra, I told them that I think about their daughter every day. I asked them to be a part of my life. A few years later, Samantha’s dad and my dad – together – walked me down the aisle at my wedding. Now her parents can count seven lives that their daughter made possible: the five people who received the gift of an organ transplant, my young son, and his little brother on the way.

It is a miracle on top of a miracle when someone who received a transplant goes on to have a child. The people who paved the way for me – a handful of dedicated researchers in Philadelphia – are nothing short of miracle workers. Thanks to them, I am one of around 100 women in the United States known to have had a baby after receiving a heart transplant.

The history of transplants and pregnancy is a difficult one. For a long time, recipients had to navigate a wild west of information. The answer to the question “Is it safe for transplant recipients to have kids?” differed depending on who you asked. The medical community warned that the complications of transplantation meant that pregnancy could be life-threatening. Some researchers even suggested that sterilization should be offered to young recipients.

I’ll never forget what one of my doctors said when I first told him I hoped to have kids. He looked at me and said that I would have to get a “tubal litigation,” or in other words, medical sterilization. I was so upset I didn’t know how to respond. Finally, I said, all it takes is the faith of a mustard seed – a small amount can move mountains.

I was on the receiving end of a big, basic problem in the medical community: extremely limited data. Researchers need large population groups to study treatments and risks, but the number of transplant recipients who go on to have children is very small in any given region.

As an example, think about immunosuppressants. Transplant recipients must take medication to suppress our immune systems for our entire lives, to lower the risk that our bodies will reject the new organ. Some of these medications are associated with a high risk of birth defects and many doctors assumed that was true of all of them. It was impossible to be certain without data.

Exactly 30 years ago, a visionary researcher saw this medical problem and decided to solve it. The Transplant Pregnancy Registry International (TPRI) based in Philadelphia collects data from transplant recipients around the world. Each year, study coordinators speak with hundreds of current and future mothers and fathers who are transplant recipients, and to their healthcare providers. In turn, they shine a light for people like me by publishing their findings for the world and sharing their research with the transplant community. They found the answer to my question: It is possible to have a safe pregnancy after receiving an organ transplant.

Since it was founded, TPRI and its collaborators have tracked 2,800 parents and 4,900 pregnancies. Now, they’re celebrating the next generation, a group of nearly 100 grandchildren. They also work with individuals like me, communicating directly with me and my medical team so we would know the research specific to my case. Their work helped my doctors care for me.

In my case, it turns out the medications I was taking were not safe for pregnancy. With TPRI’s research, my doctors were able to find a substitute prescription that was. That discovery, and others like it, made it possible for me and thousands of other recipients to have children.

Every person is different, and not every person who has a transplant can have children. But it is possible. If you have received a transplant and are considering pregnancy, you can and should contact TPRI.

I promised Samantha’s parents that I would live my life to the fullest and appreciate every day. Becoming a mom allowed me to do that. There is no stronger feeling in life than the pure, total love parents have for our children. On this Mother’s Day, there is no word that captures the gratitude I feel for the people who made it possible.

Finally, please, register as an organ and tissue donor.

Transplant Pregnancy Registry International is a division of the Gift of Life Institute, which in turn is the education, training and research arm of Gift of Life Donor Program. Also based in Philly, Gift of Life is one of the world’s leading organ procurement organization non-profits.