There is something near-miraculous about the organ donation system, which allows tens of thousands of Americans a year to give up parts of their body they no longer need to extend the lives of others.

And yet tens of thousands of viable organs are also lost each year rather than going to patients desperately in need of them. Researchers recently estimated there are only half as many donors as there are deaths with potential to donate.

Given how life-changing an organ transplant can be, and the scale of demand, how could we ensure that every potential donation finds its way to a recipient?

We tend to focus on the surgeon as the key figure in the equation. But as it turns out, the success of organ donation hinges just as much on other links in the chain.

If we supported the entire organ transplant system and held it to better account, we would ensure that more organs from the dying could become a gift of life for someone else.

Here’s how that might work.

There’s an urgent need to increase the number of organ transplants

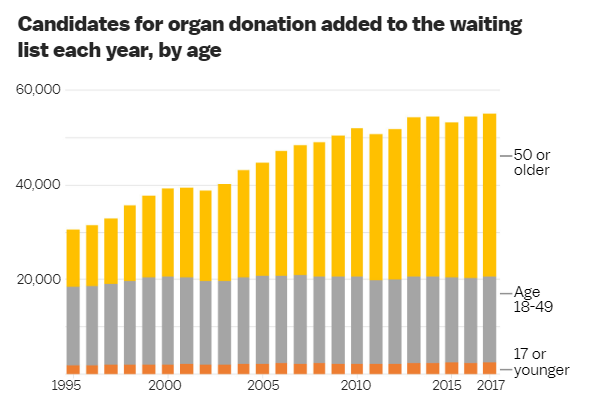

2017 was a record year for organ donation and transplantation, as the number of deceased people whose organs were recovered for donation surpassed 10,000 for the first time. Those donations, combined with organs offered by nearly 6,000 living people, together meant that 35,000 desperately ill people got lifesaving transplants.But that same year, more than 50,000 people were added to the waitlist.

Source: Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

Courtesy of Vox

Of those people currently on the US transplant waitlist, 81 percent need a kidney, 12 percent need a liver, and the rest need a heart, lung, pancreas, or intestine. They suffer from conditions as varied as diabetes, alcohol abuse, or hepatitis C, but what they have in common is that one of their vital organs is irreversibly failing.

As organs become available for transplant, they are matched with the sickest nearby patient with whom they are compatible, following a complex protocol that takes physiological and geographic factors into account. To reach the front of the line, patients may have to wait until their illness is very advanced, and, as a result, undergo surgery when they are least able to physically tolerate it.

Transplant centers control which patients are added to the list; they can be conservative in putting forward only those who they believe will benefit. Dr. Seth Karp, director of the Vanderbilt University Transplant Center, estimates that only one in 10 patients who die of liver disease in Tennessee was even on the waiting list for a liver.